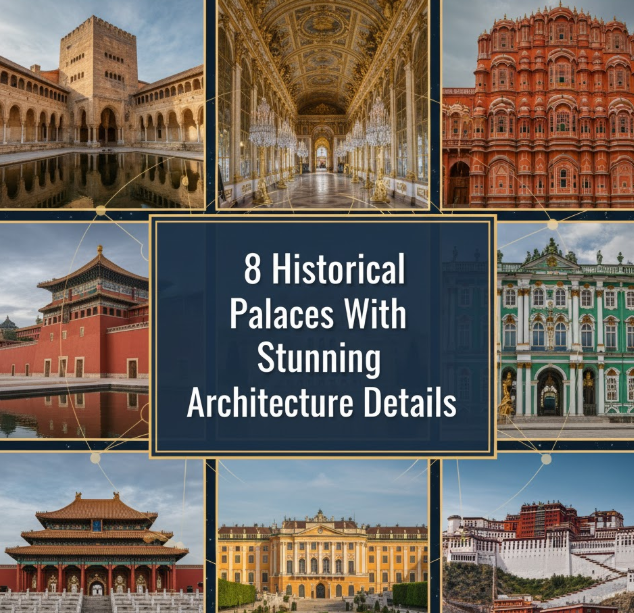

Walking through the gates of a grand palace, you enter a realm where power, artistry and human ambition conjoin in stone, gold and glass. These magnificent buildings were more than just places where kings and queens laid their heads — they were also reflections of power, wealth and national heritage that have endured for hundreds of years as witnesses to their own history.

Whether it be the sun-soaked courtyards of Spain or the frosty spires of Russia, historical palaces display not only extravagant works of art and architecture, but they also offer a testament to the incredible creativity and skill from architects and craftsmen who dedicated their livelihoods to develop something extraordinary. All the palaces harbour secrets in their walls, from secret passageways to elaborate carvings which would have taken decades to complete.

What truly sets these buildings apart isn’t their size, or the gold leaf that adorns their ceilings. It’s the smallest things — the way light meanders through stained glass windows, the mathematical exactitude of Islamic geometric patterns or the optical trickery that can be played by skillfully placed mirrors. These architectural marvels show that human greatness has always been filled with grandiosity.

In this piece, we will discover 8 extraordinary palaces from around the globe, taking an in-depth look at architectural design features that distinguish these royal homes. You will learn how builders solved engineering problems long before there was modern technology who decided on certain designs and what these palaces reveal about the societies that built them.

The Alhambra: When Math and Beauty Merge

Rising from a hill overlooking Granada in southern Spain, the Alhambra is one of Europe’s best examples of Islamic architecture. It was largely constructed in the 13th and 14th centuries under the reign of the Nasrid dynasty, and it exhibits architectural practices that continue to baffle engineers.

The Hidden Patterns of Islamic Design

To visit the Alhambra is to step into a three-dimensional mathematics textbook. The walls are adorned with geometric patterns known as “tessellations” — shapes that lock together seamlessly and leave no gaps in between. Muslim craftsmen made these patterns using just a compass and straightedge, adhering to strict Islamic prohibitions against creating representations of humans in religious spaces.

The Court of the Lions is a great example of this symbology. Twelve marble lions, one for each of the twelve tribes of Israel or the twelve months of the year surround a fountain in the center. Water conduits cut through the courtyard, representing the four rivers of paradise referenced in the Quran. Each has both symbolic and practical value.

Water Engineering That Defied Gravity

One of the most incredible parts of the Alhambra is its water system. Engineers created an intricate diagram of channels, fountains and pools that operated without pumps or electricity. They relied on gravity and carefully considered slopes to transport water throughout the complex in order to have a cooling impact on Spain’s sweltering summers.

This hydraulic genius is also seen in the gardens of the Generalife. Water flows through narrow channels known as “acequias,” which is borrowed from Roman technology but refined by Islamic builders. Trickling water served as a natural air conditioner and helped wash away stress, offering a serene environment for meditation and reflection.

Palace of Versailles: Excess At Its Best

When King Louis XIV chose to relocate his court from Paris to Versailles in 1682, he conceived not only of a palace but a political instrument for taming the French nobility and projecting French power abroad.

The Hall of Mirrors: An Optical Phenomenon

The most celebrated room in Versailles, spanning 240 feet long with 357 mirrors — an exorbitant indulgence in the 17th century, when mirrors were more valuable than paintings. Head architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart arranged these mirrors facing seventeen windows, adding a power of infinity to the hall and multiplied further the light which poured into it.

The engineers behind this design cracked a big problem. The hall links the King’s apartments to the Queen’s, and Louis XIV desired a room that could dazzle visitors while also functioning as a working hallway. Mansart transformed the relatively narrow corridor into what feels like a grand ballroom, using mirrors.

Charles Le Brun painted the ceilings of about 10,000 square feet, representing Louis XIV’s military victories and political feats. These weren’t arbitrary adornments — they were pieces of propaganda meant to keep everyone mindful of who was in charge in France.

Gardens That Redefined Landscape Architecture

The Versailles gardens were designed by André Le Nôtre with mathematical precision and optical tricks that transformed landscape architecture forever. He invented “forced perspective” — the laying out of paths and plantings to make distances seem greater than they are. From the palace, when you are looking at the Grand Canal, it appears as if the gardens extend endlessly to the horizon.

The gardens were kept in order by hundreds of workers. Gardeners had to replant their flowers multiple times a year in order to keep the blooms growing, and some 1,400 fountains were managed by engineers on an intricate hydraulic system. The “Machine de Marly” transferred water from the Seine three miles away, using no less than fourteen giant water wheels — one of the most grandiose engineering projects in its day.

Forbidden City: Architecture in a Closed Universe

China’s imperial palace for almost 500 years and residence to two dozen Ming and Qing dynasty emperors, the Forbidden City was Beijing’s absolute center of power. This huge complex encompasses 980 buildings and roughly 8,750 rooms constructed in accordance with ancient Chinese cosmology and philosophy.

The Power of Numbers and Color

The Forbidden City was constructed by Chinese architects according to concepts of spatial relationships, cosmology and numerology from the “Book of Changes” (I Ching) and feng shui. The number nine is repeated in the complex as it symbolizes the ultimate authority of the emperor. They took nine by nine as the unit for building dimensions of main palace buildings (81 parts are considered to be the supreme number).

Color was a rigid code in ancient China. Most palace buildings were tiled in yellow, the color of the emperor that commoners were prohibited from using. Red walls symbolized happiness and good luck. Blue tiling was present only on buildings of the Crown Prince, and green tiles identified libraries where knowledge resided. This color system made it possible for people to immediately grasp the building’s purpose and significance.

Earthquake-Resistant Design From the 1400s

The Forbidden City’s wooden buildings have withstood centuries of earthquakes, thanks to clever engineering. By following a Chinese carpentry method known as “dougong” — interlocking wooden brackets that slot in together without nails or glue. These brackets act like shock absorbers, bending instead of breaking during earthquakes.

Each building is perched on a plinth comprising rammed earth and stone, providing a base that evenly distributes weight. Those upturned roof corners — a Chinese architectural signature — are more than decoration. They make the roof lighter overall and allow better drainage during Beijing’s seasonal heavy rains in summer.

Topkapi Palace: An Ottoman Salute to Sophistication

Positioned on the Bosphorus strait in Istanbul, Topkapi Palace was the administrative and residential center of Ottoman Empire for more than four centuries. Unlike the European tradition of palaces that are all-in-one enormous buildings, Topkapi is composed around four courtyards with a multitude of smaller-sized buildings, itself an expression clearly stating the Ottoman ideology when it came to power and the sphere of privacy.

-

🧱 One of the longest structures ever built! Discover more: The Great Wall of China: A Marvel of Ancient Engineering

The Harem: Architecture of Secrecy and Power

The Harem at Topkapi has over 300 rooms where the Sultan’s family used to live. These spaces were constructed by architects with several security checkpoints and a maze-like layout to prevent unauthorized access. It was a fortress within a fortress, with narrow corridors, numerous doorways and guards’ rooms set in key locations.

Many walls in the Harem are decorated with Iznik tiles — hand-painted ceramic tiles that display floral designs in blues, greens and reds. Not only were they beautiful, but also the tiles were there to help keep rooms cool during Istanbul’s blistering summers. Its inherent cooling and heating properties absorbed the sun’s heat by day and released it gradually throughout the night, providing natural climate control.

Small windows of wood with delicate lattice work known as “mashrabiya” screens enabled women to see out into courtyards without being seen. They also served as a sun screen, blocking excessive heat but casting beautiful shadows that varied throughout the day. This design catered to the cultural demands of privacy combined with the need for ventilation and light.

The Acoustics of the Imperial Council Chamber

A distinctive feature of the Divan tower, where the Imperial Council was held, is its superb acoustical design. Architects crafted the domed ceiling so that voices could be heard without a trace of echo, enabling the sultan to eavesdrop on meetings from behind a screened window up above and out of sight. The proportions of the dome and dimensions of the room led to perfect sound distribution — a technology today’s concert halls still struggle to achieve.

Schönbrunn Palace: Baroque Splendor in Vienna

Austria’s Schönbrunn Palace is the epitome of Baroque architecture and built to rival Versailles as a show of Habsburg might. A yellow palace built in the 18th century with 1,441 rooms and gardens that sprawl across 500 acres.

The Great Gallery: Where Gold Intersects Light

The Grand Gallery was the ballroom and state room of the palace; in it, a young Mozart gave a concert to Empress Maria Theresa. White and gold decorations cover every surface, made from stucco lustro — polished plaster combined with marble dust that was as reflective of candlelight as marble but weighed much less.

Architects placed huge windows along both long walls, inviting natural light to fill the 130-foot-long room. Crystal chandeliers suspended from ceiling bore hundreds of candles during balls and ceremonies creating blinding light effects reflected with the help of gilded decorations around the room and mirrors. It transformed nocturnal affairs into epic displays of power and wealth.

The Palm House: Victorian Architecture, Imperial Glass and Botanical Exchange

The Schönbrunn Palm House, one of the largest greenhouses in the world, was opened in 1882. This iron and glass edifice measures 373 feet long and stands at 82 feet tall, in a display of Victorian engineering at its best. Builders employed a skeletal iron frame — a pioneering method at the time — that could accommodate far more glass than had been feasible before without compromising structural soundness.

The Palm House is equipped with an elaborate heating system involving pipes hidden under the ground which transport hot water, meaning it can remain a balmy tropical paradise even when it’s 20 degrees colder outside. Architects segmented the interior into three climatic zones — cool, temperate and tropical — enabling plants from different regions to flourish beneath one roof. This design set the standard for greenhouse construction around the globe, and it illustrated architecture’s capacity to master nature.

Mysore Palace: Indo-Saracenic Fusion

Situated in Karnataka, India, Mysore Palace is the result of a cross-pollination of Hindu, Islamic, Rajput and Gothic architectural styles to become an Indo-Saracenic style building. The current palace, finished in 1912 to replace an older wooden structure burned down by fire, displays early-20th-century innovation with traditional Indian craftsmanship.

The Kalyana Mantapa: An Uncommon Marriage Hall

The Kalyana Mantapa, the marriage hall is octagonal and is covered with a beautiful stained glass roof that has been designed to resemble a peacock. Scottish glaziers designed this work of art using more than 20,000 pieces of colored glass shaped into peacock feathers — India’s national bird. The sunlight pouring in through this ceiling has a magical effect and the floor under this dripping light is ever-changing with shades of colors.

The ceiling is supported by 68 cast iron pillars which have been twisted and decorated. These are imported pillars from England, which is symbolic of the exchange of technology and capital between Britain and India in the colonial era. This use of industrial materials in the work blended with traditional Indian embellishment to create a style that was very unique for this time.

The Durbar Hall: A Space of Alive Festivals

The Durbar Hall was the principal ceremonial chamber in the palace, where the Maharaja would meet his audiences for court functions and ceremonies. The ceiling is painted and gilt with highly worked patterns of Hindu divinities and mythological themes. This series of paintings was created over several years by Italian artist De Toma, who combines Western painting techniques with Indian themes.

The floor is polished Jaipur marble in which colored semi-precious stones have been inlaid to form geometric patterns (the technique, called “pietra dura,” was adopted from Mughal architecture). The palace is lit up with more than 100,000 light bulbs during the annual Dasara festival, making it a sight to behold from miles. This tradition, which was initiated more than a 100 years ago, is continued to this day and has made the Mysore Palace one of the most visited monuments in India.

Peterhof Palace: Russia’s Waterfall Kingdom

Peterhof Palace became Russia’s version of Versailles, when it was built by Peter the Great in the beginning of the 18th century. Set on the Gulf of Finland, this palace ensemble is a rare example of an 18th-century Baroque building in Russia designed to cope with the country’s climate and combines architectural innovation with impressive imagery associated with St Petersburg.

The Grand Cascade: Gravity-Powered Magnificence

The Grand Cascade comprises 64 fountains, 255 bronze sculptures and three waterfalls running down from the cascade’s artificial hill to the lower level of the Lower Park. And the whole system runs without pumps — it was engineered to tap into natural water pressure from springs in nearby hills. Water courses through pipes below the ground for miles until it bursts out in awesome displays.

The centerpiece Samson Fountain shows the biblical hero tearing the jaws of a lion open, as water shoots 66 feet into the air. This fountain is a monument to Russia’s victory in the Great Northern War (the lion is shown as Sweden). The bronze and gold original was stolen in World War II but recast using photographs and old plans and placed here after the war.

Winter Adaptations in Palace Design

Unlike the palaces of southern Europe, Peterhof architects had to take into account harsh Russian winters. Thick walls, more than three feet in places, insulated the interior from freezing weather. The leaded-glass windows, by contrast, had double panes — still new technology in those days — with air pockets that inhibited the transfer of heat.

The palace is equipped with complex heating systems involving massive ceramic stoves (“pech’ka”) adorned with hand-painted tiles. Built into walls and shared by rooms, these stoves generated heat for multiple spaces at once and held onto it for hours after fires burned out. This innovation enabled the palace to be warm despite Russia’s harsh winters, meaning there were no unsightly radiators or vents.

Neuschwanstein Castle: A Fairytale Constructed Using 19th Century Technology

Though often referred to as a castle, Neuschwanstein is really more of a palace completed in 1886 for King Ludwig II of Bavaria. The Romanesque Revival palace that crowns the rough wisps of rock above the village of Hohenschwangau provided Disney with his inspiration for Sleeping Beauty Castle.

Medieval Design With Victorian Technology

King Ludwig II desired a medieval fortress, but his architects used state-of-the-art 19th-century technology in virtually every aspect of the structure. Neuschwanstein was one of the first buildings to be equipped with indoor flush toilets on every floor, this in conjunction with heat and a gravity-based flushing system at the time modern sewage works. Rooms were warmed by hot-air ducts in a central heating system — a luxury few buildings had until the 20th century.

The kitchen had both hot and cold running water, with speaking tubes — a primitive intercom system — that allowed the king to issue orders from dining rooms without messengers. Electric bell systems in the palace allowed the king to call attendants to any room at a second’s notice. These were secondary to contemporary luxuries, concealed behind the medieval aesthetic, as if a modern home emerged from an ancient castle.

The Throne Room: A Dream Unfulfilled

The Throne Room is Ludwig’s grandest ambition unrealized. This two-story hall in Byzantine style was designed by architects to resemble churches Ludwig had seen during his travels in Italy. The room has murals of saints, kings and queens on the walls, a blue ceiling with golden stars and marble columns imported from Italy.

Curiously, a throne was never placed. Ludwig passed away before finishing the project, and almost immediately after his death the palace was opened to the public. The throne that should have been filled echoes the split between Ludwig’s romantic dreams and hard reality — he bankrupted Bavaria building his architectural fantasies.

Special attention was given to the acoustic design of the room. Architects designed the room to magnify both speech and music, with dome ratios and wall angles that directed sound towards an elevated throne position. Acoustic tests today verify that the room as designed would have delivered excellent sound quality, demonstrating that Ludwig’s team had some grasp of the science of acoustics even though its primary purpose in the throne room was symbolic.

Comparing Architectural Approaches

| Palace | Primary Style | Key Innovation | Construction Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alhambra | Islamic | Geometric tessellations & water engineering | 13th-14th century |

| Versailles | Baroque | Hall of Mirrors & forced perspective gardens | 17th century |

| Forbidden City | Chinese Imperial | Earthquake-proof wooden structures | 15th century |

| Topkapi | Ottoman | Layered security & Iznik tile climate control | 15th-19th century |

| Schönbrunn | Baroque | Palm House greenhouse engineering | 18th century |

| Mysore | Indo-Saracenic | Stained glass fusion & electric lights | Early 20th century |

| Peterhof | Russian Baroque | Gravity-powered fountain system | 18th century |

| Neuschwanstein | Romanesque Revival | Medieval design with Victorian technology | Late 19th century |

Common Architectural Elements Across Cultures

Although culturally, religiously and temporally distant, these palaces have some architectural commonalities. All palaces deploy symmetry as a way of projecting power and order — symmetrical wings, centered entrances, geometric gardens are all featured in structures running from China to Spain. This is a universal human liking for harmony and symmetry.

Water features are employed for practical, aesthetic and symbolic functions in all styles of gardens. From the cooling channels of the Alhambra to Peterhof’s gravity-powered fountains, architects still knew that water could regulate temperature, set a mood and signal engineering prowess. In every culture that constructed these palaces, water represented life, abundance and divine favor.

The issue of natural light control is a priority in all buildings. As a result, architects placed windows and used reflective surfaces to maximize daylight — essential before electric lighting. The Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and the stained glass in Mysore Palace are two approaches to this ideal: how to make bright, impressive spaces that seem to shimmer with divine or royal energy.

Modern Preservation Challenges

These masterworks of architecture now face unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. Climate change is also threatening buildings and other structures that were constructed in a different era, for different weather patterns. The Forbidden City’s wooden structures are damaged by higher temperatures, and Versailles’s delicate paintings and furniture are at risk from excessive humidity.

Tourism creates another dilemma. Millions of visitors each year want to have that experience, but foot traffic and body heat, as well as humidity from breath, are harmful to the fragile materials involved. Preservation teams must weigh public access against conservation requirements, and such systems are commonly introduced to provide climate control and limit the number of visitors in sensitive areas.

But today’s restoration methods rely on technology the original builders never could have fathomed. Laser scanning captures detailed 3D models of entire palace complexes, making it possible for conservators to monitor subtle changes that could signal structural issues. X-ray fluorescence in turn enables them to identify original paint color hidden beneath centuries of dirt and efforts at restoration, so that repairs can be historically accurate.

Learn more about UNESCO World Heritage Sites and their preservation efforts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which palace took the longest to construct?

The Forbidden City still holds the title, its construction stretching from 1406 to 1420 — roughly 14 years for the primary building (additions and alterations went on for centuries). Over 100,000 craftsmen and a million laborers contributed to its construction.

Can a person see all these palaces today?

Yes, all 8 palaces are now open for tourists but some of the spots are restricted to public either for conservation purpose or for security. At the Alhambra, advance reservations are required because of visitor caps instituted to safeguard the delicate structures.

Which palace is the largest?

It’s 250 acres and has 980 buildings, so the Forbidden City is by footprint the largest. But if you measure in floor area as a whole, including gardens, the title holder is Versailles with its sprawling grounds and many auxiliary buildings.

Was building these palaces expensive?

Exact figures are difficult to pinpoint because of differing currencies and economic systems, but Versailles probably clocks in as most expensive. Louis XIV spent about 2% of all of France’s GDP per year on construction and upkeep — that ends up being about $2-3 billion a year in today’s dollars.

Were these palaces even that comfortable to live in?

By modern standards, no. While splendidly comfortable, the majority of these did not have central heating (although Neuschwanstein and some others built later had) as well as having primitive sanitary facilities and little privacy. Drafty corridors, chilly winter nights and rooms that were either too hot or too cold depending on the time of year were all part and parcel of life for those who lived in palaces.

Which palace has the majority of its original decorations preserved?

Peterhof Palace was extensively damaged during World War II, but has been carefully restored to match the original designs through old photographs and other records. But the Forbidden City has the most original buildings as it was a living architecture until 1912 and does not suffer any major battle damage on its structure.

Do any of these palaces still serve as government facilities?

Actually no, all of the eight now serve primarily as museums and touristic sites, with some staging occasional state dinners or ceremonial events. The most recent transition of the Forbidden City from a working palace to museum occurred in 1925.

Modern Architecture’s Enduring Influence

These palatial structures from history continue to influence architecture in unexpected ways today. The geometric designs of the Alhambra and M.C. Escher’s work are believed to have been inspired by one another, while its influence can also be seen in modern Islamic architecture across the globe. Versailles’ garden design principles continue to shape landscape architecture, its forced perspective techniques turning up in everything from theme parks to corporate campuses.

The engineering solutions found at these palaces — passive cooling, water features powered by gravity and acoustic tricks — are being picked over by contemporary architects looking for alternatives to environmentally unfriendly design. With buildings facing a requirement to cut energy use, techniques from hundreds of years ago in palaces across the globe offer proven answers that succeeded without electricity or fossil fuel.

These buildings are a sign that good architecture is bigger than where it began. What started as a demonstration of royal might and national pride evolved into a world patrimony to us all, teaching us about engineering, craftsmanship and our common heritage. They demonstrate that when people labor to create something really special, in which they invest time, resources and imagination, it can be a treasured legacy for future generations.

So the next time you close your mouth and open your eyes to what these magnificent places were all about, or the next time you are given an opportunity to walk among them, remember that these weren’t just old buildings. You’re looking at a fine mark of human achievement: places where power, beauty and ingenuity came together to build something that outlasted the empires who built them. These are palaces that provide lasting evidence of what people can do if we have the temerity to dream in stone, gold and glass.