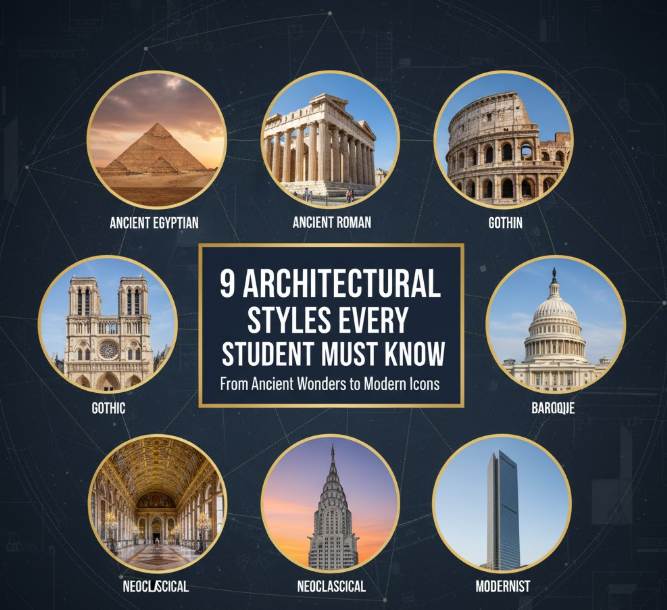

Architecture is the tale of human history. Every building around us stands for ideas, culture and its time. From ancient temples to soaring skyscrapers, the evolution of different architectural styles reflects how people lived and what they believed, and explores how cultures around the world respond to their environment with architecture. For students, understanding these styles can be the entrée not only to specific buildings, but also to history, art and society.

This manual surveys nine crucial aspects of architectural style that have affected our milieu. But whether you’re into design, history or simply curious about the buildings that make up your daily landscape, knowing these styles will influence the way you see the world. Each style has its distinct characteristic elements, historical background and enduring influences on contemporary design. Here are the architectural movements every student should know and appreciate.

Greek Architecture: The Basis of Western Design

Geometrical Greek architecture originated sometime around 900 BCE to the first century CE, which established design principles we currently follow. The ancient Greeks said that buildings should embody harmony, balance and mathematical perfection. They built temples, theaters and public works that depicted their gods and democratic values.

The column is the most distinctive element of Greek architecture. Greeks had three major forms of columns – Doric (no-nonsense, strong), Ionic (scroll at the top) and Corinthian (much more decorative with leaves). These columns were not decorative they used careful engineering to hold up enormous stone roofs.

The Parthenon in Athens is the ideal form of Greek architecture. Constructed between 447 and 432 BCE, this temple reflects the Greeks’ knowledge of optical tricks. The columns splay very gently outward, the base curves upward at the corners to give a look of perfect straightness from afar. Greek architects also used the “golden ratio,” a mathematical ratio that produces naturally appealing designs.

Greek buildings usually had a gable roof with a triangular facade-shaped section known as the pediment and carved decorations were placed along the rim of the pediment, sometimes illustrating mythological content. They were made of marble and limestone, which could be carved in fine detail. The Greeks also led the way with symmetry — if you drew a line down the middle of their buildings, they would be mirror images of each other.

Roman Architecture: Engineering Meets Grandeur

Roman architecture borrowed ideas from the Greeks and gave rise to new engineering marvels. Over 900 years, from 500 BCE to around 400 CE, they built an empire and filled it with monuments that expressed their power and themselves as a people. Where the Greeks designed temples, the Romans made things, designing aqueducts and punching holes in mountains for roads and building great bathhouses to cleanse their own industrial wastes.

They invented concrete, which enabled them to construct bigger and more complex buildings than ever before. They knew how to build with the arch and vault and dome — curved forms that could cover vast distances without columns obstructing the middle. The concrete dome of the Pantheon in Rome is still the world’s largest unreinforced solid concrete dome two thousand years after it was built.

Roman buildings served public life. The gladiator mecca of the Colosseum could seat 50,000 and boasted sophisticated crowd control with 80 gates. Roman aqueducts sent water over valleys at careful gradients — and some of them still work. They constructed roads, forums (public squares), and basilicas, which united and ordered the empire.

The Romans adopted Greek columns, though theirs were more ornamental than structural. They blended styles and added their own inventions, such as the Composite order, which combined Ionic and Corinthian elements. Roman architecture articulated imperial dominance through scale — the grandiosity of their buildings were meant to astonish and intimidate.

Gothic Architecture: Reaching Toward Heaven

During the 12th-16th centuries, gothic architecture was widespread in Europe mostly in religious edifices. This approach arose in medieval France and traveled across Europe, begetting some of the most spectacular cathedrals in history. Gothic architecture was a spiritual movement — builders sought to create spaces that would raise human thought to God.

The Gothic style is epitomized by the pointed arch. Unlike the circular Roman arch, which had to take a broad shape to facilitate such actions, the pointed arch could be more narrow and therefore act on walls that were much taller. This invention resulted in soaring interior spaces that were bathed in light. Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and Chartres Cathedral are testaments to how Gothic builders formed vertical spaces that made people feel tiny in the presence of the divine.

These are external support structures that resemble stone arms holding the walls up; they are called flying buttresses. These stretched Gothic cathedrals skyward with huge stained-glass windows rather than thick walls. The tinted glass would narrate biblical stories to those who could not read, turning buildings into illustrated books. Stained-glass designs, such as rose windows, which are circular, assumed a dominant role in the facade of Gothic cathedrals.

Gothic buildings include ribbed vaults (crossing stone arches on ceilings), tall spires that stretch to the sky and delicate stone carvings called tracery. Gargoyles fulfilled the dual role of being decorative water spouts and of symbolizing the evil beyond that keeps sacred places pure. Style was marked by emphasis on verticality and light, with the goal to instill a sense of peace and religious devotion.

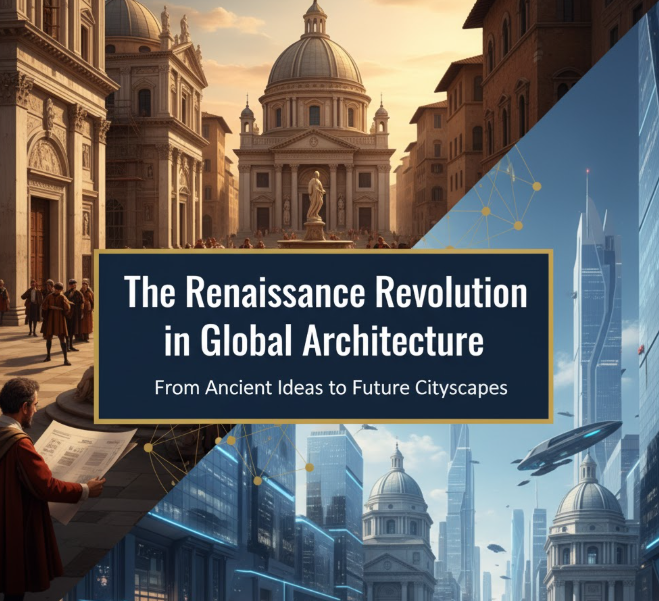

Renaissance Architecture: Revival of Classical Styles

Renaissance architecture was lauded in 15th-century Italy as society learned knowledge from ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Rebirth is the meaning of “Renaissance,” and architects examined classical ruins to figure out how ancient structures were proportioned and built. During this time some of history’s most famous architects — among them Filippo Brunelleschi and Andrea Palladio — were active.

Renaissance architecture highlighted symmetry, proportion and geometry. The architects used mathematical ratios to mold harmonious spaces that themselves reflected humanist philosophy — the idea that humans could understand and influence their world through reason. Whereas the Gothic builders had climbed upwards, the Renaissance artists put pictures together in horizontal harmony.

The dome reappeared as an important architectural issue. Brunelleschi’s dome for Florence Cathedral resolves issues that had stumped builders for decades, seamlessly building an octagonal-shaped dome without relying on temporary wooden supports. The classical column orders were also revitalized but they were applied with a better understanding and more creativity.

Renaissance buildings were characterized by use of rusticated stonework (rough-textured blocks on the walls at lower stories), rounded arches, and geometry. Palaces and churches were centralized, with ideal ratios. Ideal Renaissance values: symmetrical layout, classical columns, proportion and fitting into the surrounding scenery as seen in Villa Rotonda by Palladio. This style has shaped the architecture of much of the world, and is regarded as the first time modernism appeared in architectural form; it also served to define several attitudes towards urban planning that still exist to this day.

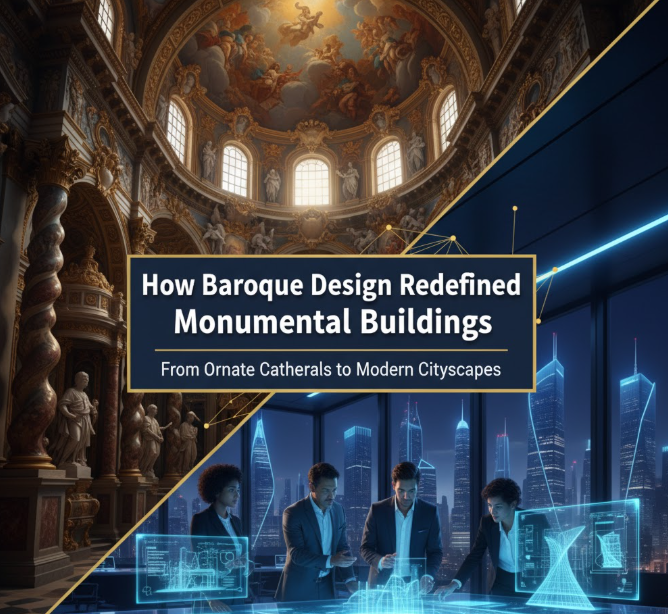

Baroque Architecture: Drama and Movement

Baroque architecture sprouted throughout Europe from the late 16th to the early 18th centuries. If Renaissance architecture was serene and balanced, Baroque architecture was emotional and dramatic. The Catholic Church encouraged this style during the Counter-Reformation, adopting it for courts — a secular use in which overwhelmingly huge spaces enticed attendees with awe-inspiring design.

Baroque architecture followed the same lines of thought; the dynamics of building stepped forward and became a separation into various vaulted, domed bays. Walls undulated, appearing to flow. Interiors treated light dramatically — veiled windows and gilded surfaces cast illuminating effects that seemed uncanny. The Palace of Versailles, in France, embodies typical forms and elements associated with the Baroque, including colossal size, a grand structure covering an extensive area (symmetry), the front’s tens even hundreds of columns and rich ornamentation designed to impress anyone who enters or sees it surrounded by ample grounds uniting architecture with the landscape-gardens representing reason while wilderness beyond represents unreason.

Baroque architects adored contrast: light and darkness, convexities of form and concavities; plain surfaces versus elaborately ornamented. They also employed trompe l’oeil (illusions painted to look three-dimensional) on ceilings, so they would appear bigger and more heavenly. Pillars twisted or formed clusters. Sculpture was incorporated into architectural features.

Buildings such as St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome epitomize Baroque values. The embracing gesture of Bernini’s colonnade invites in sacral space. Baroque architects, on the other hand, designed entire urban landscapes — arranging fountains, statues and buildings to provide dramatic vistas. This was a mode that expressed power, wealth and spiritual authority through nothing less than excess of the senses.

Neoclassical Architecture: Reason and the Values of Republics

Reaction to Baroque excess, Neoclassical architecture began in the mid-18th century as a reaction against the more ornate and decorative Baroque style. Influenced by archaeological findings in Pompeii and Herculaneum, architects were attracted once again to simplicity of Greek and Roman. This was contemporary with the Enlightenment and American and French democratic revolutions, so it articulated values such as reason, order and republican virtue.

Typically, they are characterized by clean lines and symmetrical shapes as well as classical elements used properly according to ancient guidelines. Porticos (covered entries) are carried by columns with good proportions. Pediments feature simple geometric decorations. The exhibition’s cumulative effect is dignified and restrained rather than emotional.

Neoclassical aesthetics were enshrined in public office buildings around the world, as they linked modern democracies with these ancient Greek and Roman republics. The United States Capitol, the British Museum and Panthéon in Paris are three of many prominent structures based on neoclassical architecture. White or other light color is used, horizontal emphasis is sought for and impressive but reasonable effect achieved.

Neoclassical architects subjected classical buildings to careful study, measuring ruins and even consulting texts from the ancient world. They eschewed Baroque curves and decoration in favor of straight lines and minimal ornament. This yielded architecture that appeared authoritative and permanent — just what institutions that hope to exist for generations would want.

Victorian Architecture: Industrial Age Diversity

Victorian architecture represents styles that were popular during Queen Victoria’s reign in Britain and the British colonies, between 1837–1901. This was not a single style, however, but an array of revival movements made possible thanks to Industrial Revolution technology. Mass production brought new building materials and techniques — iron framing, for example — as well as transportation that connected Americans to a wider world.

Extravagant decoration is the hallmark of Victorian buildings. Architects combined Gothic and Classical with exotic motifs for exuberant designs. Asymmetrical facades, towers, bay windows and wraparound porches were common on homes. Factory-made ornaments — brackets, corbels and lace-like decorative trim — were used lavishly. The result was unique, romantic buildings that spoke to owners’ wealth and demeanor.

For churches and universities the style became an accepted guide on how the reproduction of Gothic architecture could be achieved, building designs in which there was no attempt to reproduce an existing Gothic building. Mediterranean villa designs were introduced in the temperate regions under an Italianate roof with wide eaves. The Queen Anne style was characterized by ornate rooflines, turrets and surface treatments.

Victorian architects were not afraid of color, applying polychrome brickwork (patterns in which bricks are different colors) and painting “painted ladies” in contrasting hues. They used new materials such as cast iron for decorative railings and structural reinforcement. Buildings from the Victorian era are richly ornamented; they reflect the new tramways and electric lighting, and confident faith in industry combined with growing city prosperity, interest in historic styles.

Modern Architecture: Form Follows Function

Modern style transformed architectural design beginning early in the 20th century. Architects eschewed historic ornament, and claimed that buildings ought to reveal honestly what they were used for and how they were made. The style’s clean lines and lack of decoration had proponents leaning toward simple geometric forms, open interior plans, and the use of new materials such as steel, glass, and reinforced concrete.

“Form follows function” is a condensing of Modern thought. Instead of decorating styles, Modern architects shaped buildings from the inside out — according to how people would use them. Steel-frame buildings didn’t require walls to bear loads, so they could be primarily glass. This resulted in transparent structure that links inside and outside.

Another manifestation of the style was following 1920s-30s International Style, with white walls and flat roofs, similar shaped windows and simplicity of design. Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion are examples of this. Buildings were on pilotis (columns that elevated structures) and the ground floors remained open. Roof gardens took nature to the city.

Contemporary architects held that good design should be the privilege of all, not only the wealthy. They invented mass-producible housing and furniture. Prairie Style homes by Frank Lloyd Wright melded the architecture with the landscape, employing natural materials and horizontal lines that echoed America’s Midwest. The Bauhaus school emphasized the fusion between art, craft and technology in order to produce functional beauty.

Postmodern Architecture: Playful Rebellion

Postmodern architecture arose in the later 1960s-1970s as a response to perceived limitations of modern architecture. If the Modernists turned their back on history and decoration, then Postmodernism welcomed them both back into the fold with a wink and snigger. They also argued that buildings could be fun and colorful, reference historical styles and employ contemporary technology.

Postmodern structures do not have simple shapes, bright colors and decorative structural elements on their facade. Architects went out of their way to mix wrong styles and make odd couplings. Michael Graves’s Portland Building transplants classical proportions and colorful ornament from an office in a modern building. The AT&T Building (now Sony Tower) by Philip Johnson boasts a broken pediment top that seems taken from colonial furniture in a nod to a sense of humor about the past.

They really believed that architecture should speak to guys on the street, not just other architects. They employed familiar shapes and references to make buildings more accessible and memorable. Robert Venturi took a look at Las Vegas and told us that commercial “vernacular” architecture had something to teach serious architects about symbolism and communication.

This aesthetic favored complexity and contradiction over the simplicity of Modernism. Buildings could be both symmetrical and asymmetrical at the same time. They might allude to Roman temples and pop art in the same building. Postmodern architecture meant personality, humor and historical awareness was returning to contemporary building design, although critics complained that it could be superficial and lacked Modern integrity.

Comparing the Nine Architectural Styles

| Style | Period | Characteristics | Key Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greek | c. 900 BCE–1st century CE | Columns (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), pediments, symmetry, marble | Parthenon, Athens |

| Roman | c. 500 BCE–400 CE | Concrete, arches, domes, public works, engineering | Pantheon, Colosseum |

| Gothic | 12th-16th centuries | Pointed arches, flying buttresses, stained glass, verticality | Notre Dame, Chartres |

| Renaissance | 15th-17th centuries | Symmetry, proportion, domes, classical revival | Florence Cathedral, Villa Rotonda |

| Baroque | Late 16th-early 18th centuries | Drama, movement, ornament, light effects | Palace of Versailles, St. Peter’s |

| Neoclassical | Mid 18th-19th centuries | Classical simplicity, columns, pediments, symmetry | U.S. Capitol, British Museum |

| Victorian | 1837-1901 | Eclectic revivals, ornament, color, asymmetry | Victorian “painted ladies” |

| Modern | Early to mid 20th century | Function over form, geometric purity, steel and glass | Villa Savoye |

| Postmodern | 1960s-1990s | Historical references, colorfulness, playfulness | Portland Building |

Why These Styles Matter Today

Knowing the styles of architecture helps students read the built world just as you would a book. Buildings share a society’s likes and dislikes: Greeks liked democracy and gods, Romans liked engineering power, Gothic masons made manifest religious belief and Modernists wagered everything on functional simplicity.

More recent buildings often sample several styles or quote from earlier architecture. By reading these references, architectural design can also be better understood. New public buildings frequently rely on Neoclassical architecture to induce a sense of vigor and authority. Churches may add Gothic elements to lend an air of spirituality. If your students can think critically about why an architect took a certain style approach from among the many historically available options, then they’re golden.

One of the aspects that interests me very much about these movements has to do with educational issues, e.g. in all architecture schools, we still have to study these movements, because we believe there are principles derived from design which outlast time. The Greek golden ratio still gives you the most pleasing proportions. The concrete revolution: when innovations in Roman construction were built directly into the pour. Functionalist thought of the modern architects is applicable to sustainable design today. Twice, each style added enduring ideas to the store of architectural knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which architectural style is in more demand today?

Today, architecture has no monopolizing style. And many architects apply Modern principles — clean lines, glass, sustainable materials — but use regional influences and historical references. Neo-Modern and sustainable “green” architecture are also being stressed, with energy conservation and environmental responsibility taking precedence over purely formal considerations.

How can I spot architectural styles in my neighborhood?

Begin by looking at distinctive features: the Classical column type indicates a style akin to the Classic, pointed arches are indicative of an influence from Gothic, ornate decoration is sure to denote Victorian or Baroque, and plain geometric shapes mean Modern architecture. Consider the building’s age (sometimes simply carved onto a cornerstone), its window shapes, type of roof and amount of ornamental detail. Contact local historical societies for maps of homes worth walking by.

Were architects once so servile to a style?

Architects frequently mixed styles together, or were transitory between movements. Buildings often mix and match elements from various periods, especially when they’ve been renovated. Revival influences (including Gothic Revival in the Victorian era) reinterpreted historical styles using modern materials and design. Architectures don’t “flip” overnight, they evolve.

Which architectural style is the most significant?

The “most important” style is not one, but rather all provided innovations of value. This architectural approach laid down proportional systems that are still taught today. Roman engineering was only made possible by the ability to undertake such large-scale public work. Modern architecture changed how we look at function and space. The significance of each architecture style, you see, depends on which element of architecture is most important to you: aesthetics, engineering and construction prowess, societal impact or historical legacy.

Can you use old architectural styles with new builds?

Absolutely. Many modern architects allude to the past in their work, incorporating traditional styles with modern materials and techniques. This results in buildings that are respectful of context and tradition, while addressing the needs of today. University buildings often feature Gothic or Classical elements to blend in with campus architecture. The challenge is to incorporate mindfully, rather than just mimic.

What factors determine what architectural style is used on a building?

A lot of things come into play when determining what style will be used: the building’s use, budget, location, cultural considerations, the client’s desires and how the architect sees it. For gravitas, government buildings might go with Neoclassical style, while tech companies tend toward Modern glass designs that suggest innovation. In certain neighborhoods, historical preservation laws require new buildings to fit in with the existing neighborhood.

Conclusion

These nine architectural archetypes are the foundations from which humans began designing and building structures. From Greek columns to Postmodern playfulness, the style of any era is a reflection of that era’s values, technological capabilities and artistic sensibilities. Learning these styles changes how students perceive the world around them, as mundane buildings become not just historical records but works of art.

Architecture communicates across centuries. The principles laid down by the ancient Greeks continue to generate beautiful proportions. Roman engineering and construction techniques make modern building possible. Gothic builders’ aspirations made time-immortal places. The beauty follows logical rules, as Renaissance mathematicians proved. Each style was evolved from what had been learned before and added to it.

For students, that is not what it means to learn architectural history. It is about learning human creativity, cultural values and how societies portray themselves through built environments. Whether or not you ever become an architect, or merely know more knowledgeably which end of a hammer to use, knowing these nine styles — consciously, sensitively, critically — makes our actual physical world that much richer. Next time you see a building, take a closer look — it has tales to tell about the people who built it and designed it and the climate that created an environment for both. Architecture is visible history, and now you are equipped to read its language.