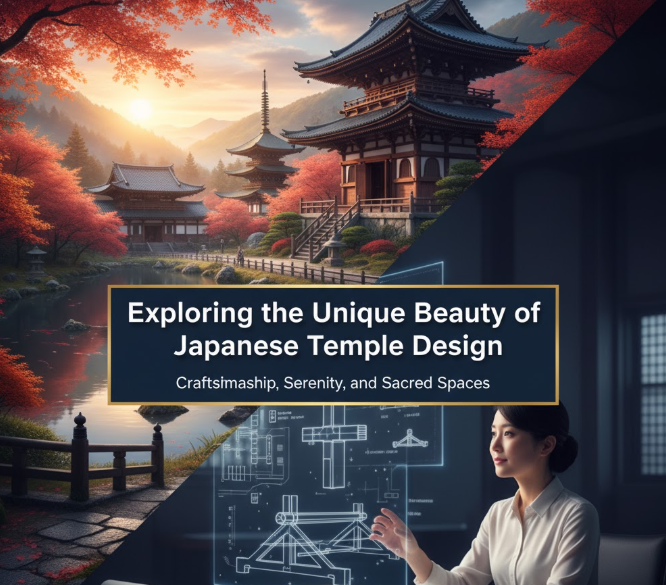

A happy thing happens when you set foot in a Japanese temple. The air feels different. The colors, the shapes and even the silence appear to be telling a tale thousands of years old. Japanese temple design isn’t just about building a place for worship; it’s designing an environment that integrates people, nature and the spiritual world. It took centuries to carefully design these sacred places, combining religious beliefs and artistic visions with great practical wisdom in such a way that millions of visitors continue to be inspired by them annually.

Everything in a Japanese temple—from the monumental gates defining the entrance to hidden gardens that bloom with flowers of each passing season—serves a purpose. Because whether you’re in Japan, hoping to visit or just interested in world architecture, to understand these temples is to gaze through a window into Japanese culture and philosophy — and artistic genius. So come with me on a trip into the absorbing world of Japanese temple art and learn why these buildings are so extraordinary.

Why Do Japanese Temples Look Different From Those in Other Religions?

Japanese temples are different from such worldwide that is the churches or mosque whatever. The distinction is not a small matter of style — it involves an entirely different conception of sacred space.

Most Japanese temples are Buddhist, a religion that was introduced from China and Korea to Japan in the 6th century. But the Japanese didn’t just take what they learned and replicate it. They blended Buddhist thought with their native Shinto beliefs, and created something new entirely. This mix of styles manifests itself in everything from the materials for the building to the manner in which temples fit into their surroundings.

Japanese temples have a horizontal beauty, not the verticality we seem to seek in religious architecture among Western people, with bell towers and steeples ascending toward the heavens. They nestle into the earth and merge with the surroundings. This was in communing with nature’s ephemerality, not wearing it down. The temples are made of natural materials: wood, stone and paper that age well, integrating the building into its surroundings.

Elements of a Japanese Temple

Strolling through a Japanese temple compound is like turning the pages of a potted epic in stone and wood. And each part has its own significance and purpose.

The Sanmon Gate: Your First Step Into Sacred Space

Even before you arrive at the main temple, there is the sanmon, or main gate. It’s no mere entrance — it is a threshold between the everyday world and the realm of the sacred. The gate typically contains two stories; the upper floor contain statues of Buddhist guardians or venerable religious figures.

The sanmon gate can be a daunting structure, painted bright or vermillion red or in natural wood tones. When you move past this moment, you cross through a symbolic threshold from worldly concerns to inward spiritual reflection. Some gates are huge wooden doors that open only on rare occasions, making them seem even more important.

The Main Hall: So Much History, So Little Faith

The hondo, or main hall, is the heart of any temple. This is where the main Buddha statue stands guard, and where monks and visitors come to pray and meditate. The main hall sits elevated on the platform, and you must walk up a flight of stone steps that lift you physically as you move toward the consecrated image within.

Inside, the mood is somber and contemplative. Incense smoke twists and drifts through the air; golden statues glow in flickering candlelight. The ceiling may be embellished with intricate murals or carvings, and the tiled roof is supported by thick wooden pillars. The halls are designed to feel both grand and intimate all at once.

The Pagoda: Reaching Toward Enlightenment

The pagoda is probably the most famous element of Japanese temple architecture. Now, these multi-storied towers acting as a casket for Buddhist relics or script are here all across and once over time served as golden reliquaries containing Buddha ashes or writings. Traditional Japanese pagodas vary from three to five or seven stories, each story representing certain steps in the Buddhist’s path to enlightenment.

The great revelatory thing about pagodas, however, is their engineering. They are designed to survive earthquakes through a central pillar that hangs from the top floor, giving the building freedom to sway. This ancient, earthquake-proof design demonstrates that the practical genius of Japanese builders who labored without modern technology.

The Garden: Nature as Spiritual Guide

Temple gardens are special because they aren’t simply for show — but the garden is also a teacher. Japanese temple gardens are designed rock, water, plants and paths that express spiritual concepts as well as creating an idealized version of a natural landscape.

Some include meticulously raked gravel intended to represent ocean waves with larger stones standing in for islands or mountains. Others are ponds containing koi carp, stone lanterns and bridges that lead visitors to sakura or spring blossom, koroyu (autumn leaves) or yuki no yohei (winter snow). The idea is that as you stroll over these gardens it should provide a meditative and peaceful spiritual quality to the mind.

Colors and Materials That Offer a Narrative

The materials and colors used in building Japanese temples aren’t picked at random—they have deep symbolic significance.

Wood: The Living Material

Japanese temples are typically made of wood, which can be an eye opener for those familiar with stone cathedrals or brick mosques. The Japanese used wood because they had plenty in their densely forested isles, but also because wood conveys life and impermanence — core Buddhist concepts.

Wood is available in various types and each one has its own function. Hinoki cypress, which is valued for its beauty and resistance to decay, is a common choice for key structures. The wood is also left raw or treated with oils to emphasize its grain, showcasing the material’s beauty in process. The wood ages, forming a rich patina that the Japanese find more beautiful than when it was new.

The Power of Red and Gold

When temples do employ color, red and gold are the primary colors. Vermillion red, used on gates, pillars and railings has both practical and symbolic significance. From the color, which is made from mercury sulfide covering wood to protect it from insects and weather, while also symbolizing life force and the ability to ward off evil spirits.

Gold is seen in statuary ornament, temple fittings and painting details. It carries the meanings of awakening, clarity and transcendent insight of Buddhist teachings. When red and gold are used in combination you come to feel the visual message is one which proclaims this space is sacred.

Tiles and Thatch: From Overhead They Must Be Protected

Temple roofs are composed of either ceramic tiles or thatch, both of which have unique personalities. Ceramic tiles, typically in gray or black hues, are hardy and fireproof. They overlap so efficiently that the rain runs off them in fetching slope-shoulder rooflines.

Some older or provincial temples are topped by thatched roofs of rice straw or miscanthus grass. They do need to be replaced often, but insulate well and have a softer, more natural look in nature.

The Way Temples Shift With the Seasons

One of the loveliest things about Japanese temple architecture is how they fit into the seasons. In Japanese culture, to be proud of seasonal variations as the practice of meditation on the passage of life and death, they are also structured in a way which lets us witness there great natural rhythm.

| Season | Temple Experience | Highlights of the Year |

|---|---|---|

| Spring | Pink clouds enveloping temple buildings from cherry blossoms | Hanami (flower viewing), fresh green growth |

| Summer | Shade and cool under the trees | Open corridors allow breezes, hydrangea flowers |

| Autumn | Red and orange leaves set on fire around temples | Momijigari (leaf viewing), harvests |

| Winter | Temples turn into monochrome sumi-e paintings | Clean outlines are drawn in simple gardens, fewer tourists create silence |

Every seasonal view is taken into full consideration in the temple garden design. A place that is filled with cherry blossoms in April may be the home of irises by June, lotus flowers by August and chrysanthemums by November. This predictable progression of seasons reminds visitors to see beauty in all time, even as it marches on and slips through our fingers.

Well-Known Temple Design Styles Throughout the History of Japan

Japanese temple architecture has developed over the centuries, proving vital to many of its defining styles and including variations from various regions.

Asuka/Nara Styles (6th-8th centuries A.D.)

Most of the earliest Japanese temples were copies of Chinese and Korean designs. This layout had buildings lined up along a central axis, and had buildings built symmetrically. The Horyū-ji in Nara, the world’s oldest surviving wooden structure, also shows this woodwork techniques and constantly rebuilt structures.

Early temples were less elaborate in their construction and decoration relative to their later counterparts. The emphasis was on functional space for the new Buddhist practices, which Japanese society at large had yet to become accustomed to.

Heian Period Elegance (9th-12th Centuries)

With the emergence of a national culture, temple design was also improved and refined through craftsmen of Japan. For building rooflines, there were more curves and for interiors there were intricate paintings, sculptures.

It was also the heyday of Pure Land Buddhism, which led to many temples with gardens for imitating Buddhist paradise. These “paradise gardens” had large ponds with islands symbolizing the journey to enlightenment over the ocean of suffering.

Zen Simplicity (12th-16th Centuries)

When Zen Buddhism was imported from China, a newly radical form of temple architecture came along with it. Zen temples were characterized by simplicity, natural materials and the beauty of empty space. Buildings grew more coiffed-up, with tidy lines and very little flourishes.

So too did the Zen rock gardens—arrangements of stones and raked gravel that could be contemplated, inviting meditation. The iconic rock garden at Kyoto’s Ryoan-ji temple, featuring fifteen stones set in such a way that one is perpetually concealed from view, epitomizes this aesthetic.

Edo Period Elaboration (17th-19th Centuries)

The Edo era was a time of peace and prosperity, leading to bigger temple building. Decorations suddenly grew complex as carvers turned out intricate designs of dragons, flowers and mythological creatures on all surfaces. Color and gold leaf were more freely employed — with dazzling visual effects.

The Toshogu Shrine in Nikko is a classic example with its riot of colors, gilt and carvings that decorate every part of the buildings. This methodology is a celebration to hard work and skill.

Tiny Details That Change the Game

Japanese temple design works as well as it does because of the breathless attention to a million smaller details that all come together into an almost indistinguishable whole.

Decorative Elements for Your Roof That Beautify and Protect

In place of these, a long ornamental tile is used on the corners and ridges of temple roofs. These are not just for ornament — they also keep weather out of the roof structure, as well as evil spirits. Demon faces, dragon heads and mythical beings gape down from roof corners, transforming practical architecture into protective guardians.

Even the curved rooflines have a practical connotation: “They’re designed to maximize light,” Mr. Kaelin said. The rise at the corners is high enough to enable swift runoff of rain, and yet not such that water would be easily shed toward the building’s foundations. But these curves also result in luscious lines that feel like they are trying to pry the building up into space, even as it remains focused on a horizontal plane.

Wooden Brackets: Engineering as Art

If you’re up close to where temple roofs meet their column supports, you see elaborate bracket systems called tokyō. These intricate wooden connections distribute the weight of the roof among several points without nails or metallic connectors.

No one mastered this structural necessity better than the Japanese. Brackets are chiseled and arranged with artistic design and enchanting appeal reflecting their engineering utility. The number and complexity of bracket double-stacks can provide a clue as to the significance of a building.

Bell Towers: The Sound of Sanctity

In the majority of temple compounds there is a bell tower containing a massive bronze bell. These bells, known as bonsho, are rung to signal time, herald ceremonies or on special occasions like New Year’s Eve when temples sound their bells 108 times to represent cleansing the 108 worldly desires that bring human suffering.

The bell towers chosen were architecturally wondrous themselves: open structures that allow sound to carry but provides protection to the bells from rain and snow. They range from basic posts with a roof to elaborate buildings that reflect the dimensions and shape of the main hall.

Stone Lanterns: Lighting the Path

Throughout temple grounds, stone lanterns – known as toro – line pathways and dot gardens. Once practical sources of light, they are now symbolic elements to lead not just footsteps but spiritual paths.

Each lantern adheres to traditional design rules, with designated parts representing the elements of Buddhist cosmology — the base as earth, the post as water, the fire box as fire, the closed roof section as wind and its finial a sky or emptiness ornament. Even these utilitarian things have layers of meaning.

Why Temples Use Natural Settings

Japanese temples are rarely set apart, but become part of the natural setting in which they’re placed, the environment enhancing both buildings and landscape.

Mountains as Sacred Backdrops

Countless famous temples cling to mountainsides, or are perched on hilltops above valleys. This placement isn’t accidental. Mountains — considered as homes for gods and ancestors — have long been the source of spiritual inspiration in Japanese culture.

Erecting temples on or near mountains to some extent links Buddhist activity with older practices of nature worship. The trek to these temples is the exertion of pursuing spirituality, and the awe-inspiring places of worship serve as a challenge—a literal climbing in order to visualize the spiritual climb towards enlightenment.

Water Features for Life and Reflection

Water features in the form of ponds, streams and purification fountains are found throughout the temple complex. Beyond its practical functions, water serves as a symbol of purity and the spread of Buddhist teachings into the world.

For example, in temple ponds, there is usually nice touch of artificial settings such as arranged stones to let water sound—splattering drops or trickles or smooth flow between the rock. And that adds to the atmosphere as well. The surface of the water also form reflections, which makes close buildings and trees two times striking, more full of layers and oriental beauty.

Trees as Living History

Trees within the temple compounds are ancient living reminders of times past. Some of the cedars and ginkgos are more than a thousand years old, standing witness to centuries of worshippers and historical events.

These trees also offer shade and seasonally varying foliage, as well as adding vertical elements to contrast with the horizontal lines of temple structures. Sacred items in their own right, the trees are surrounded by sacred ropes called shimenawa and receive protection from numerous temples.

Modern Challenges and Preservation Efforts

Preserving wooden temples in this modern era is a difficult task which require devoted experts.

The Cycle of Renewal

Wooden temples are not like rock-cut ones, which can stand for thousands of years with little care. The Japanese have embraced this requirement as an advantage to maintain traditional handcrafting not as a weakness of products.

Large temples may be subject to renovation, rebuilding or partial restoration when they are vandalized or destroyed. This ritual, known as shikinen sengu, means traditional construction methods are handed down from master craftsmen to apprentices. When Ise Grand Shrine is reconstructed every 20 years, it keeps alive craftsmanship of woodworking that would have been worth losing.

Balancing Tourism and Tranquility

Even the most popular temples now have millions of visitors each year — a blessing and a curse. Entrance fees pay for maintenance, but crowds can be ruinous to delicate structures and disruptive of the meditative calm that a temple is supposed to offer.

Some temples now follow controlled entry and exit systems, set walking routes, and special early-morning or evening open hours for tourists looking to have a more peaceful experience. The challenge of accessibility versus preservation continues the ongoing debate regarding the balance between accessibility and preservation.

Climate Change and Traditional Materials

Contemporary environmental changes are now impacting on the traditional raw materials for construction. With higher humidity, stronger storms and shifting insect life, the wooden structures that define our neighborhoods are being placed at risk – challenging us to find modern ways of protecting them while remaining true to their classic look.

Today, conservators have the benefit of sophisticated scientific analysis to determine how materials age and deteriorate, as well as help them develop preservation strategies that complement but don’t replace traditional methods with modern materials that might seem out-of-place.

What to Know Before You Go to Temples

Visiting Japanese temples is an amazing experience, but know the etiquette and you can show that little bit more respect whilst getting even more out of your visit.

Basic Temple Manners

Slip off your shoes before entering temple buildings — you’ll notice racks or shelves have been left for this purpose. Dress modestly, avoiding revealing clothing. Of course we must also keep our voices low, and our phone ringers off.

Near the entrance is a purification fountain where you can ladle water over your hands with one hand and into your mouth (don’t drink directly from the ladle or let it touch your lips) with the other. This act of cleansing readies you to enter sacred space.

Photography Guidelines

A lot of temples are okay with photography in open areas, but not while inside buildings or around certain sacred items. Never take photos without a sign, or ask for permission. Avoid flash photography which can cause harm to the old paintings and textile.

Just remind yourself that temples are working religious spaces, not just touristic ones. If you come across monks or worshippers praying, give them space and respect instead of using them as photo opportunities.

Best Times to Visit

Morning visits hold a number of benefits — less people, better light for photos and watching monks take part in morning rituals. Some temples open their gates early morning before visiting hours.

Being there for festivals or events is a special experience, but crowds will be bigger. Every temple has its own ceremony calendar and seasonal highlights you might as well plan around.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a temple and a shrine in Japan?

Temples (tera or ji) are Buddhist, while shrines (jinja) adhere to Shinto. You can usually distinguish between the two by their entrances — temples have gates called sanmon, and shrines have torii gates (consisting of two vertical posts that frame two horizontal crossbars). Buddhist temples usually enshrine statues of Buddha, while Shinto shrines display objects that are connected to kami (deities). Both are integral to the Japanese spiritual life, and its people often attend both sides without sensing any dissonance.

Japanese temples are made of wood instead of stone – why?

Japan is very forested. Japan has a lot of forests and not many good rocks to build with, so wood is obviously the best building material. Wood also squares with Buddhist ideas around impermanence — nothing is permanent, and that’s not a problem but the nature of being. Wooden buildings are also more earthquake-ready, able to flex with the ground’s movement and absorb shocks rather than falling down like stone buildings. Wooden temples are continuously maintained, eventually reconstructed, and the tradition of ancient crafts thus carries over from one generation to another.

Can anybody go to Japanese temples, or are they only for Buddhists?

The majority of temples in Japan receive everyone regardless of their faith. It’s Japan, with a long and proud history of religious tolerance and cultural interpenetration. Guests just owe it to the places they’re visiting to show respect by practicing proper etiquette, remaining silent in sacred venues and remembering that these are working religious sites. Some temples have entrance fees (usually nominal amounts used for maintenance), and others will ask for donations. Some private or monastic temples are closed to the public, but most are open.

How old are Japan’s oldest temples?

The earliest temples were built in the 7th century. The Horyu-ji temple near Nara, established in 607 CE has the world’s oldest existing wooden structure. But as shrines are periodically rebuilt, exact dating can be tricky. Some of the site’s temple buildings stand as they have for over 1,400 years, while others are reconstructed according to their original designs.

What are those curved shapes on temple roofs?

Those curved rooflines have a practical as well as purely aesthetic function. The upward sweep at the corners allows rain and snow to slough off quickly, preserving the wooden structure underneath. The curves also keep rainwater from falling too close to the building’s foundation. The curves aesthetically dial your eye upwards, giving the impression that the building is floating and being pulled towards heaven — visual expressions of Buddhist ideas about transcendence and enlightenment. The amount of the curve usually denotes the age and style period of the temple.

Do people even still construct new temples in traditional style?

Yes, new temples are still built using old designs and methods, albeit less often than previously. When new temples are built or old ones renovated, architects and artisans often purposefully use traditional methods to retain these crafts. But today building codes may demand some compromises, such as hidden steel reinforcements or updated fire prevention systems even when the visible structure is in a more traditional style.

The Legacy of the Temple Form

Japanese temple architecture is one of the supreme achievements not just of Asian art but also world art, a perfect blending of spiritual purpose, practical utility, and aesthetic beauty. And yet these buildings school us that really great design has to do not only with how stuff looks, but how people feel about it (and inhabit it), and how it fits its surroundings, and also serves an artful function over centuries.

The values that inform temple design are not limited to the world of buildings, but rather carry valuably over into other realms of life. They represent a philosophy of balance, mindfulness and the beauty in simplicity.

Whether you travel to celebrated landmarks like Kyoto’s Golden Pavilion temples, stumble upon mountain shrines in Japan’s countryside, or even if you only explore these stunning constructions through photos and descriptions alone, Japanese temple design can open your eyes to a new way of seeing the world. Every curved roofline, every stone in a garden, and every piece of weathered wooden pillar holds some reflection about the human quest for meaning, beauty and connection to something greater than we are.

In a world of rapid change and throwaway architecture, they remind us that some things are worth making with care, looking after with hard work and preserving for those to come. They’re the proof that when we make with purpose and respect for tradition, we can create objects that outlast their own era and reach deep into something universal about what it is to be human. The peculiar beauty of this ordinary temple in Japan still excites us, because it moves our hearts and spirits, not just our eye.