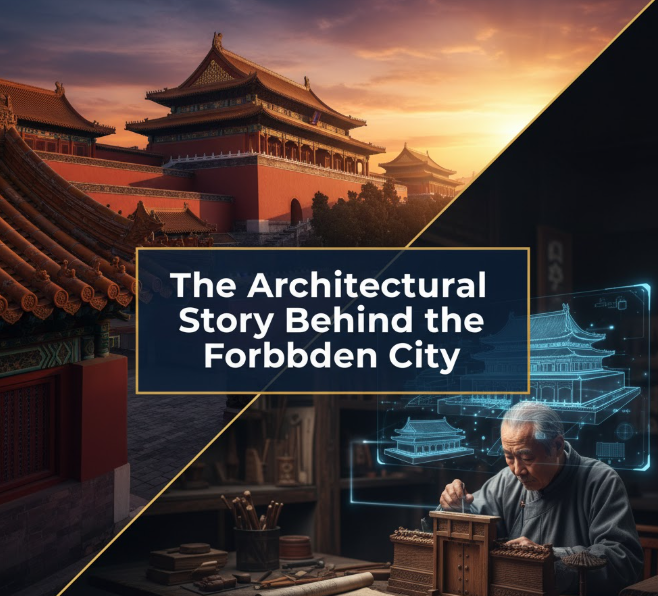

When you face the massive red walls of Beijing’s Forbidden City you’re not just standing in front of an old palace. You’re looking at one of humanity’s most stunning engineering feats — a place that millions of workers slaved over for more than 14 years to build. For almost 500 years this vast complex was home to Chinese emperors, a story of brilliant design, subtle meaning and secrets most visitors never fathom.

I don’t mean to be hyperbolic, but the Forbidden City is not just big—it’s colossal. Scatter 980 buildings over 180 acres, every one of them meticulously designed with a specific intent. That here, at this place — one corner among many crisscrossing the metropolis, one of dozens of vibrant colors drawing crowds to their portals; and a number, 88. Every corner, every color and every number in this place has its own story about ancient Chinese beliefs, power and the links between heaven and earth. Today, we’re going to step back in time to unravel the incredible architectural story of this UNESCO World Heritage site – and also find out why it is still one of the most magnificent buildings ever made.

Why They Built a City Only for the Emperor

In 1406, Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty did that very thing. He wanted to shift China’s capital from Nanjing, the setting for his Yellow Mountain paradise, to Beijing, and he needed a palace fitting an emperor. (That’s what Chinese emperors called themselves.) But this would be no ordinary palace. Yongle saw a full city in a city where just the sheer scale would exhibit to the world that China was powerful.

The emperor assembled the finest architects, artisans and laborers in all of China. More than one million workers contributed to the project, among whom around 100,000 were skilled craftsmen. They hauled materials from the farthest reaches of the empire — enormous logs from forests in southwest China, special stones from quarries hundreds of miles distant and the best clay for those eye-catching yellow roof tiles you see everywhere.

It was built over 14 years, from 1406 to 1420. To put that in perspective, they constructed something larger than 100 football fields — all without modern machinery. Workers deployed simple tools, animal power and incredible human determination. In the winter they poured water on these roads, creating ice slides, and slid massive stone blocks weighing more than 200 tons down them.

The Master Plan: How the Roots of Chinese Philosophy Rendered Every Detail

It wasn’t just that architects didn’t plunk down buildings randomly. Each and every detail of the Forbidden City was in accordance with ancient Chinese rules regarding how the universe functioned. The biggest idea was Feng Shui, or wind and water. This tradition, millennia old, was predicated on the idea of harmonizing buildings with their natural surroundings.

The entire compound is oriented towards the south, which traditionally in Chinese culture was the most auspicious direction. The throne of the emperor sat in the north, facing south, so he could look toward warmth and light. Just to the north of the Forbidden City is a man-made hill Jingshan, constructed explicitly because the palace needed protection from evil spirits that purportedly came from that direction.

The layout is on a perfect north-south axis that bisects Beijing. This axis embodied the relationship between the emperor and heaven. Everything important took place on this line — the key buildings, the grandest ceremonies, even the daily walk of the emperor followed this sacred pathway.

Another fundamental idea was yin and yang — the balance of opposites. The Forbidden City is divided into two primary parts: the Outer Court (yang, symbolizing heaven and public life) and the Inner Court (yin, symbolizing earth and private life). This division wasn’t merely symbolic; it set the people apart and divided what could occur where.

What Colors Say: The Meaning Behind What You Wear

Lose yourself in the Forbidden City and colors will appear in certain positions. Nothing was painted randomly. Each color had special meaning in Chinese culture and served its purpose.

Yellow dominates the rooflines. Those shiny, yellow-glazed tiles were not just pretty — they were divine. In Ancient China, yellow was the emperor’s color because it represented the center of the universe and ultimate power. The ordinary person couldn’t put down yellow in his buildings. The only anomalies were a handful of green-tiled buildings, where the imperial library (green was symbolic of wood, which scholars took to the heart) and princes studied.

The walls are almost entirely covered in red, as are the columns. In Chinese culture, this bright hue symbolized good luck and happiness. But red also signified fire, and, according to Chinese elements theory, fire could defeat metal — symbolically protecting the emperor from weapons and wounds.

Everything is gilt-edged: or, at least so with all edifices of note. Gold represented wealth and status, but it also symbolized the earth in Chinese philosophy. Those little golden accoutrements you see jutting out from roof corners, door knockers and ornamental fixtures weren’t just for flair; they were a statement of imperial power.

The white marble steps and promenades formed a strong contrast. White was a symbol of purity and it served to reflect light, brightening the courtyards. These marble daises served to raise up vital structures as well, bringing the emperor closer to heaven.

The Magical Number: Why Nines Are Everywhere

Tally up the door knockers on major gates, and you get nine rows of nine — 81 in all. This isn’t a coincidence. Nine is considered the peak single-digit number, carrying with it associations in Chinese culture of ultimate yang (masculine force) and eternity.

The entire Forbidden City is said to have 9,999.5 rooms. Why the half room? Legend has pure heaven with 10,000 rooms, and the emperor — who was pretty heavenly himself as the Son of Heaven — didn’t want to be disrespectful by replicating heaven’s perfection. About 8,700 rooms are actually counted in modern surveys, but the symbolic number turned into a staple of the palace’s mythology.

Nine appears everywhere:

- Major stairways have nine levels

- Important ceremonies involved nine stages

- The emperor’s robes had nine dragons on it

- Palace doors had nine lines of nine brass nails

- Key buildings in multiples of nine

The obsession with nine even filtered into everyday life. Officials would bow before the emperor with nine kowtows (deep bows). Important documents required nine seals. There were even nine dishes or a multiple thereof served to the emperor at meals.

Building the Impossible: Engineering Genius

The architects faced enormous challenges. How do you build a building that can hold up during earthquakes in an area that has so many of them? How do you heat enormous halls in frigid Beijing winters? What are some methods to fireproof wood? The solutions they came up with demonstrate a degree of engineering ingenuity that remains impressive to experts today.

Earthquake-Proof Construction

Old Chinese builders created a means of construction called dougong — interlocking wood brackets fitted together without nails and glue. These brackets act like seismic shock absorbers in earthquakes. The wooden elements can teeter back and forth, flexing to absorb the shaking instead of snapping or shattering. Many of the buildings in the Forbidden City have withstood centuries of earthquakes for this reason.

Smart Heating Systems

Beijing winters are brutally cold, dipping below freezing for months. The architects designed an underfloor heating system called huoqiang. Workers lit fires in chambers placed at the periphery of rooms, and smoke and heat would be drawn through channels beneath the floor before being expelled by chimneys. The emperor and his family stayed warm, this early version of radiant floor heating did not fill rooms with smoke.

Fire Prevention

Wooden buildings were most scared of fire. The Forbidden City suffered from several major fires over the centuries, but architects were smart about safety. At the complex resonated large bronze water vats, painted to a burnished gold color and called, in Japanese, “protective vats”—a total of 308. In winter, fires would be lit underneath the vats by guards to keep the water from freezing. In the summer, that water was left ready to battle fires.

The layout of the buildings also made it easier to contain the spread of fire. Broad courtyards isolated larger buildings as a fire prevention measure. The fact that the main courtyards had no trees wasn’t simply for ceremonial reasons—it kept fires from leaping across buildings via tree branches.

The Three Great Halls: Homes of Power

At the center of the Forbidden City are three grand halls on a three-tiered marble terrace. These complexes served as the seat of Chinese government for many centuries.

The largest and most important is the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian). This is where emperors were crowned, celebrated important festivals and performed the most momentous ceremonies. The hall is 210 feet wide and 120 feet deep, with a roof that is nearly 115 feet high. Inside is the Dragon Throne, located in the very middle of the Forbidden City and, symbolically, at the center of the whole Chinese universe.

The throne room is very detailed. In the ceiling, above the throne is a carved dragon pursuing a pearl. This dragon served a special function—if a non-imperial blood sat on the throne, story had it that the dragon would come alive and kill the pretender. The roof is supported by twenty-four massive golden pillars which symbolize the 24 solar terms of Chinese culture.

The Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe Dian) was where the emperor made his last preparations before ceremonies. Smaller, with beautiful carvings was a square building of this kind. The emperor would rehearse speeches here, drill rituals and receive up-to-the-minute reports from the courtiers.

The Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe Dian) was used for imperial banquets and the highest level of imperial examinations. Those who passed these excruciatingly hard tests could become senior government officials. Behind this hall is a marble ramp weighing more than 200 tons with detailed carvings of dragons. Workers transported this single piece of stone more than 40 miles, on ice roads during the winter.

The Inner Court’s Secrets: Living Quarters

Behind the grand ceremonial halls, however, was the Inner Court where the emperor, empresses and concubines actually lived and were attended by servants. This was the region that contained the northern part of the Forbidden City and its architecture style was very different—more minimal, with gardens, smaller buildings, and quieter courtyards.

Heavenly Purity Palace (Qianqing Gong) was the emperor’s bedroom in Ming Dynasty. Later, Qing Dynasty emperors employed it for receiving officials as well as for everyday government business. Although it was a private area, this building was as splendid as the ceremonial halls, with intricate designs on their ceilings and valued decorations.

The Hall of Union (Jiaotai Dian) was located between the emperor’s and empress’s palaces, representing their union. This building contained the imperial seals — 25 jade stamps that legitimized official documents. It also housed a significant water clock and other timepieces — keeping accurate time was, after all, an imperial task.

The empress resided in the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning Gong). The architecture here incorporated elements not found in other buildings, such as a special heated platform bed known as a kang, typical of northern Chinese homes. That demonstrated that even with all the splendor, the royal family still included practical, comfortable touches in its private quarters.

Gardens: Over the Walls, Into the Woods

The Imperial Garden (Yuhua Yuan), which occupies about seven acres of land in the northern part, comprises a planning where the structured formality is contrasted with a more organic and relaxed aesthetic. Artificial mountains, old trees, pavilions and ornamental ponds form a peaceful enclosure in which the emperor’s family could retire from court life.

The garden designers adhered to principles different from those of the palace architects. Instead of straight lines, symmetry and rigid acres, they contrived serpentine paths, surprises around each bend and hidden corners. This was in keeping with the Chinese garden philosophy that spaces should keep revealing themselves slowly, always offering new views.

In the garden there are 20 pavilions of different design and use. Some were used as reading rooms, some to watch the moon or a particular season. The Pavilion of Ten Thousand Springs has a rounded roof and is surrounded by a reflecting pool that provides beautiful symmetrical reflections.

Old growth cypress trees, some more than 400 years old, cast shadows and form a canopy. These are the trees that saw the whole of Qing – and they live to tell. The garden also contains a rock mountain constructed with rare rocks purchased from Lake Tai, known for their unique formations formed by water erosion.

Walls, Gates and Moats: The Security System

The Forbidden City was called the “forbidden” city because it was closed to commoners (i.e. forbidden!). The security setup to protect the emperor comprised various layers of physical barriers.

The entire complex is circled by a gigantic wall, 26 feet high and over two miles long. This is no mere wall — it’s thick (almost 30 feet at the base) and covered in yellow tile because this is some important wall. In each corner, there is a watchtower with vistas on all sides.

The moat, 170 feet wide, forms a barrier beyond the wall. This moat, known as the Golden Water River, also had a practical side — it was used to fight fires and for cooling effect in the heat of summer.

The walls are punctuated by four enormous gates, one on each side of the city, oriented to north, south, east and west. The southern gate, known as the Meridian Gate (Wumen) is used as the front entrance. This gate is designed to be as wide as it can be with a unique U-shape and 5 openings. The middle aperture was reserved solely for the emperor. High-ranking persons entered by the side passages, and those of a lower rank passed through the door in the wings.

Within there are further gates and walls, sections that limit movement and access around the complex. There were guards at each gate and strict rules about who could enter. High-ranking members could not even roam freely—they would take predetermined paths to particular buildings where their duties were located.

Architectural Features and Details

| Feature | Symbolism/Purpose |

|---|---|

| Yellow Tiles | Imperial power, center of universe |

| Red Walls | Good luck, happiness, fire protection |

| Double Eaves | Added protection, status |

| Upturned Roof Ends | Protection from evil, water drainage |

| Bronze Lions | Guardianship, power |

| Dragon Motifs | Imperial authority, control over nature |

| Nine-Dragon Wall | Imperial protection |

| Dragon & Phoenix | Balance of power |

| Raised Stone Ramps | Ceremonial procession, status |

Daily Life Within the Walls

The layout makes more sense when you think about the life that took place within these walls each and every day. At its zenith, around 9,000 people lived in the Forbidden City — the emperor and his family and concubines; servants and eunuchs; a private army of guards.

Everybody observed strict rules about where they could go. The design of the buildings were used to symbolize this social hierarchy. Servants would enter through little side doors and down corridors that are concealed from general view. Concubines of higher status lived in better decorated buildings closer to the emperor’s quarters. The empress’s palace was also situated in the most dignified location at the Inner Court.

There were thousands of eunuchs — men who were castrated to serve in the palace. They had their own lodging in simpler buildings adjoining the walls. Even though they were dwelling in a work of architectural art, the majority of servants never glimpsed the grandest halls or most ornate quarters.

Imperial children resided in separate quarters with their mothers and their attendants. When they were older, princes attended special establishments to be trained by tutors. This system was facilitated by the architecture, which had physical constraints to prevent people of different social rankings from mingling too close.

Changes Through Dynasties

The Forbidden City was the home to 24 different emperors of two separate dynasties – the Ming Dynasty (14 emperors) and the Qing Dynasty (10 emperors). Every dynasty left its own mark while respecting the original blueprint.

The fundamental layout and most of the major buildings were built during Ming Dynasty (1420–1644). Their best-known architectural style was large-scale and colorful. When the Qing Dynasty seized control in 1644, it retained the fundamental structure but added elements to reflect Manchu culture.

The Manchurian-speaking Qing emperors followed the practice. Tibetan Buddhist temples were added, new gardens designed, and a few buildings redesigned to include elements from home. They added heated kang platforms to residential quarters, which were not originally found in palaces of the Ming.

Various emperors also restored and rebuilt parts devastated by fire. The Forbidden City suffered extensive fires in 1557, 1597, 1644 and many other years. Every reconstruction offered the chance to develop fireproofing and modernize styles while remaining true to the general design approach.

Preservation and Modern Challenges

The Forbidden City continues to be the Palace Museum today, and it attracts over 15 million visitors each year. And that creates special challenges for preserving 600-year-old architecture. Modern preservationists work to keep buildings looking good using period materials and methods.

We now know the fascinating details of how the building was once constructed, in recent restoration works. Workers found the ancient architects had used a special kind of mortar originally made from rice flour mixed with lime which had generated incredibly strong bonds. Other wooden beams were coated in special oils that had helped preserve them for hundreds of years.

Climate change poses new threats. The wooden structures and paintings are damaged by humidity. Extreme weather events strain the ancient drainage systems. Preservationists are also challenged to balance historic authenticity with contemporary protections.

The museum is now limiting daily visitors to 80,000 in order to cut down on wear and tear on floors and structures. A number of fragile buildings are still closed to visitors. Sophisticated monitoring devices record temperatures, humidity and structural integrity around the complex.

Impact on Global Architecture

The Forbidden City had a significant architectural effect on much of Asia and beyond. That design language spread to Korea, Vietnam and Japan, where you can find similarly laid-out palaces and similar styles of decoration. The focus on axial planning, spatial planning and color symbolism would become a particularly East Asian characteristic of palace design.

Even today, modern architects look to the Forbidden City for inspiration. The sustainable design features — from natural ventilation to solar orientation and water management — provide lessons for today’s green building. We’ve studied and adapted the earthquake-resistant wood-framing methods.

Today’s Chinese architects will often use elements of Forbidden City design to decorate a new building, mating the old with the new. Similar roof styles, color schemes and courtyard layouts can be seen in significant government buildings, museums and cultural centers across China. For more information on UNESCO World Heritage sites and their preservation, visit UNESCO’s official website.

Numbers That Tell the Story

| Measurement | Details |

|---|---|

| Area | 180 acres / 720,000 m² |

| Buildings | 980 preserved |

| Construction Duration | 1406-1420 |

| Wall Length | 3.8 kilometers / 2.4 miles |

| Wall Height | 8 meters / 26 feet |

| Wall Width | 9 meters / 30 feet at base |

| Moat Width | 52 meters / 170 feet |

| Workforce | Around 1 million workers, 100,000 skilled craftsmen |

| Emperors | 24 (Ming and Qing Dynasties) |

| Years as Imperial Residence | 492 years (1420-1912) |

| Current Annual Visitors | More than 15 million |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why was the Forbidden City named as “Forbidden”?

The title of palace meant that the general public was never allowed to enter under any circumstances without direct permission. The gates were only passed by the emperor, his family, invited guests and official business. Suspected infiltrators risked harsh punishment if they were caught, including death. Its Chinese name, Zijin Cheng means “Purple Forbidden City.”

How many rooms does the Forbidden City really have?

Though legend has it that there are 9,999.5 rooms, these days surveys put the number at about 8,700 rooms. So where is the confusion? The Chinese counted any space between four pillars a room unlike in modern times. The symbolic 9,999.5 was more significant than the literal count: it conveyed the emperor’s humility before heaven while asserting maximum earthly authority.

Has any conqueror ever actually busted into the Forbidden City?

Yes, several times throughout history. The greatest of such was in 1644 when the rebel forces seized Beijing and caused the collapse of the Ming Dynasty. The final Ming emperor killed himself at Jingshan Hill, which looms immediately to the north of the palace. The incoming Qing Dynasty subsequently made the Forbidden City its political seat for almost three centuries, ruling from 1644 until 1912. The compound was occupied in part by foreign forces during the Boxer Rebellion (1900).

And why did they build with so much wood instead of stone?

Wooden building is a firm choice in Chinese traditional construction, the wood was deeply rooted in various climatic and cultural circumstances. While in many places suitable building stone was lacking, wood was plentiful. More importantly, from the perspective of Chinese philosophy, wood was a living material that had breath and deflected with nature. Wood as a material also had the benefit of flexibility, and could withstand earthquakes better than rigid stone structures. Stonework was used for foundations, terraces and ornamentation.

Do you see everything in the Forbidden City today?

No, large parts are still closed to visitors. About 50 percent of the complex is open to tourists, including the most important ceremonial and living spaces. Conservation requirements and continued restoration work, as well as the importance of maintaining vulnerable structures, have kept many buildings closed. The Palace Museum has been gradually opening new sections as restoration work is finished, but some areas may never be opened to the general public owing to their fragile condition.

What in such confined quarters kept the emperor from becoming bored?

For someone who has spent his entire life living within its 180 acres, the Forbidden City can seem confined. Emperors were entertained by a variety of activities. There were also open-air entertainments, such as the Imperial Garden. They amassed art, studied with scholars, practiced calligraphy and watched theatrical performances in special courtyard theaters. They also possessed vast libraries, could hunt in special enclosures and gave lavish banquets. Various seasons brought their own festivals and ceremonies, which mixed up the routine.

The Legacy That Stands Today

When you walk through the Forbidden City today, it feels like another world. The architecture is not merely an exhibition of ancient Chinese skill — it’s a history lesson about what one civilization believed when it came to power, heaven, earth and the place of humanity in the universe. Every building, color and decorative flourish was drawn from millennia of philosophical reflection and practical wisdom.

The builders executed something that has endured wars, revolutions, earthquakes and fires. The miracle of the Forbidden City’s architecture isn’t just that you can walk paths long trodden by emperors 500 years dead, stand in courtyards where history pivoted and gaze up at yellow-tiled roofs that represented supreme power: It’s that you still can.

This immense complex reminds us that it is possible to provide not one but several reasons for great architecture. It protects and shields, of course, but it also educates, edifies and connects us to something more meaningful than ourselves. The Forbidden City was constructed to exalt emperors and separate them from the masses. Oddly enough, now it’s what brings people from all over the globe together and makes them look at everything that human beings can accomplish when they use skill, vision and determination.

Though you never go to Beijing, the architectural tale of the Forbidden City has lessons that transcend history books. It’s an inspiring reminder that great accomplishments take planning, patience and purpose. It demonstrates that the most successful designs fulfill practical requirements and have enduring significance. And it also shows that if you build something carefully, and thoughtfully inherit the knowledge of those who came before you, your creation can well outlast your lifetime.

Today, the Forbidden City is not just a museum or tourist spot, it’s a teacher. Its walls, halls and courtyards still tell that story of how architecture can seize a civilization’s dreams and make them real — one brick, beam and tile at a time.