Each time you pass a soaring cathedral with pointed arches reaching skyward, its stained-glass windows flinging color onto the floor and stone gargoyles peering from its edges, centuries of design come alive. Gothic architecture did not spring fully formed from the middle age brow but developed and evolved over centuries, leaving mankind some of the most awe inspiring buildings it’s ever created.

This trip back in time shows how builders, artisans and communities stretched what was possible with stone, glass and faith. Nestled in the centuries since the flowering of medieval France, Gothic architecture is a story about human aspirations as much as divine inspirations—cosmic cathedrals and fantasy figures set in stone carved from earth.

Where Everything Began: The Birth of Gothic Architecture

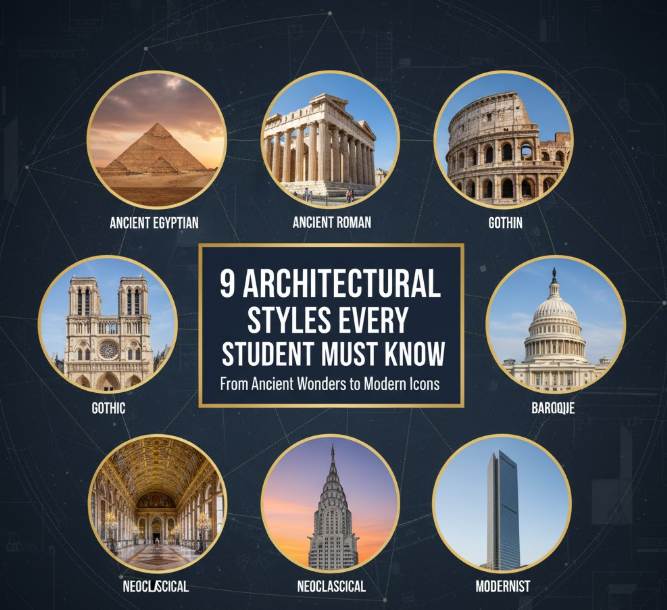

Gothic architecture first appeared in the area around Paris in 12th century France (Île-de-France). Preceding Gothic architecture was Romanesque, which had been known to be characterized with thick walled buildings, small windows and rounded arches. Interior of a Romanesque-style church felt dark and oppressive.

That all changed around 1137 when Abbot Suger started renovating the Abbey of Saint-Denis just outside Paris. Suger, who aimed to build a light-filled church as he equated sunlight with the presence of God. His vision helped shape revolutionary building techniques that would define Gothic architecture for centuries.

The new style disseminated rapidly throughout Europe. Builders in England, Germany, Spain and Italy would adopt and adjust these methods within a few decades, each of them adding its own local flavor to the Gothic mix.

The Main Characteristics of Gothic Buildings

Pointed Arches: The Beginnings of Gothic Design

Unlike the round arches of Romanesque buildings, Gothic designers favored pointed arches. And it wasn’t just a matter of style: Pointed arches were stronger and more flexible. They would be able to accommodate more weight, and distribute pressure downward rather than outward. This allowed builders to construct taller and taller structures secure in the confidence that walls wouldn’t fall over.

Flying Buttresses: The Secret Support System

Flying buttresses are exterior braces that resemble stone arms reaching out to bear the walls’ heavy weight. These architectural advancements meant that builders could make thin walls with large windows, as the buttresses took on a significant portion of the building’s weight. Before flying buttresses, which could bear some of the weight from the roof and thus allow for thinner walls, walls had to be very thick in order to support a heavy roof on top—giving little space for windows.

Ribbed Vaults: Touching Heaven on the Ceiling

Gothic ceilings had ribbed vaults—intersecting stone arches that formed a gangling web above your head. These ribs channeled weight down to key locations in the walls, rendering the ceiling stronger and more visually ornate. When you walk into a Gothic cathedral and look straight up, you feel as if you’re standing within a stone forest.

Stained Glass Windows: Walls of Light

Gothic builders were able to replace massive stone walls with huge stained-glass windows because of this improved support system. These were not mere ornamentation—they doubled as “books” for the illiterate, recounting biblical narratives in bright images. The rose windows, circular stained-glass masterpieces, would later become Gothic cathedrals’ trademark features.

Vertical Focus—Trying to Touch the Divine

In Gothic architecture all leads upward. High spires and ceilings and up-reaching windows give a towering presence that lifts eyes—not to mention spirits—upward. This vertical focus was in line with medieval ideas of having heaven above, and a wish to construct buildings that linked earth and sky.

Three Important Stages of Gothic Architecture

| Period | Time Frame | Features | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Gothic | 1140-1200 | Use of Pointed Arches, Basic Flying Buttresses, Simplified ornamentation | Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1163), Laon Cathedral |

| High Gothic | 1200-1280 | Perfected Flying Buttress systems, Large Rose Windows, Great Height | Chartres Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Sainte-Chapelle |

| Late Gothic (Rayonnant & Flamboyant) | 1280-1500 | Elaborate ornamentation, Flame-like Tracery, Extreme Verticality | Cologne Cathedral, Milan Cathedral, King’s College Chapel |

Early Gothic: Learning and Experimenting

Early Gothic buildings were laboratory tests. Architects were innovating how to put pointed arches and flying buttresses to good use. Notre-Dame de Paris, begun in 1163, embodies this experimental period. The builders studied how to build it as they went, sometimes adjusting things as they built when they discovered better ways.

In primitive Gothic the church was far from being free of Romanesque forms. The walls were not as thin as later buildings, and the decoration was relatively plain compared to what was to follow. But the seeds of invention had been sown.

High Gothic: The Golden Age

The highest development of Gothic was reached in the 13th century. Builders had refined the trick and were comfortable taking it to its limits. Of obvious strong interest is Chartres Cathedral, reconstructed following a fire in 1194, and the pinnacle of High Gothic. Its stained glass windows encompass some 20,000 square feet, splashing the interior in hues.

Reims Cathedral, the site of French coronations, reveals the attention given to harmony and proportion during this time. Each of these elements is related and tied into one—sculptures, windows, arches, decorations—all are gathered in the whole. High Gothic struck the happy medium between the constructive and beautiful.

Late Gothic: Pushing the Limits

Gothic architecture became more ornate as it developed. The Rayonnant style (French for “radiant”) featured even more glass, and fine stone tracery. Windows grew so large that walls all but vanished.

In the 15th century, decoration was pushed to an extreme in the Flamboyant style. Stone tracery resembled flickering flames (hence “flamboyant”). The buildings threw me with their deeply engraved pieces, twisted spires and added patterns. It went too far for some critics, but others took it to be the apotheosis of Gothic craftsmanship.

Regional Variations: Gothic Goes Global

French Gothic: Where It Started

French Gothic was still the measuring stick against which all other styles were judged. French cathedrals were characterized by height, light and architectural unity. The emphasis remained on the production of spiritual spaces that elicited wonder through heroic dimensions and luminous beauty.

English Gothic: Horizontal Lines and Perpendicular Style

English builders adjusted Gothic to their native tastes and materials. English cathedrals were often less soaring than they were long, with distinct perpendicular tracery—vertical lines in windows that produced a different visual effect from those of France. The English Gothic Cathedral is represented by Canterbury, Salisbury and Westminster Abbey.

Fan vaulting was also unique to the English, with ribs radiating out from a central point, like a fan. The ceiling of King’s College Chapel in Cambridge is a powerful example.

German Gothic: Towering Ambition

German Gothic went tall—really tall. The twin spires of Cologne Cathedral rise 515 feet into the sky. German builders also adored elaborate woodwork and sculpture, populating their churches with high-maintenance altarpieces and ornament.

Italian Gothic: Classical Influence

Gothic architecture was never as much of a passion in Italy as it was farther north in Europe. Italian builders, working among Roman ruins, chose to focus on classical elements. Dominating the cologne, with its pinnacles and forest of spires, Milan Cathedral is typical of Italian Gothic integration of northern gothic styles with southern external decorations.

Italian Gothic churches were likely to have patterned marble facings rather than the posting of carved stone portal sculptures found in France and England. You can see this in the Duomo of Florence with its green, white and pink marble façade.

Spanish Gothic: Moorish Influence

Spanish Gothic took influences from Islamic architecture (which had been in Spain for over 700 years) and combined them with the existing stylistic motifs. The fusion produced a distinctive style, with geometric patterns, ornamental brickwork, and horseshoe arches mixed with the more familiar Gothic motifs. Burgos Cathedral and Toledo Cathedral are typical examples of the characteristically Spanish Gothic.

The Building of a Gothic Cathedral: A Human Perspective

It wasn’t quick or easy to build a Gothic cathedral. Most of them required decades—many verging on a century, with some even lasting centuries. The work was the product of lifetimes from many generations of laborers, artisans, artists.

The Workforce

The buildings were designed by master masons and construction overseen. These were highly trained professionals who knew geometry, engineering and architecture, they were architects plus engineers in the medieval world. Hundreds of stonemasons, carvers, glaziers (glass workers), carpenters, blacksmiths and laborers stood under them.

Constructing a great cathedral used up much of the available labor in a medieval city. It was risky stuff—falls, injuries and accidents were all but routine. Workers organized guilds to shield their interests and keep company knowledge secret.

Materials and Methods

The task of quarrying stone, moving it the site and heaving it up into place was monumental. Workers had at their disposal simple implements—hammers, chisels, wooden scaffolding and rope-and-pulley systems. There was no machinery, only human and animal muscle power.

Stone carvers had populated it with thousands of sculptures—saints, angels, demons, animals and plants. These were not mere decorative carvings; they told stories and taught lessons. Many sculptures stashed high up on the side of the building, where people could scarcely make them out, had been cut with just as much care as those meant to be seen. Medieval artisans thought that God could see everything they made.

Financing the Dream

Whose magnificent projects the absolutely were paid for? Funding was provided from a variety of sources: donations from wealthy individuals, the Church, royal benefactors and ordinary people. Town vied against town to construct the most impressive cathedral, which was of itself considered a source of civic pride. Some donated what they could; the wealthy gave gold and land, and the poor gave their labor or a few coins.

Some cathedrals hawked “indulgences” that promised spiritual rewards for donors. Others contained valuable relics that drew pilgrims, whose alms helped pay for the construction and upkeep.

Decline and Revival of the Gothic Style

Why Gothic Faded

Gothic architecture went out of vogue by the 16th century. This was the Renaissance, and it introduced new influences from Italy, with a focus on classical Greek and Roman styles. Gothic architecture was derided as “barbaric” by Renaissance architects (the word “Gothic” itself originally referred to the Goths, who invaded Rome).

Gothic architecture was likewise influenced by the Protestant Reformation. Protestant churches typically wanted simpler designs without ornate motifs; demand for Gothic structures was thus limited.

The Gothic Revival: Old Style, New Age

Gothic architecture enjoyed a revival in the 18th and 19th centuries. Authors, artists and architects were interested in medieval era. The Romantic movement exulted in feeling and in nature and in the past—and Gothic architecture was a perfect fit.

Britain led the Gothic Revival. The rebuilt British Parliament building (Palace of Westminster) of London was a prominent example of Gothic Revival design. According to the architect, Augustus Pugin, Gothic architecture kept was morally superior to other styles and thus there were heated arguments about architecture and society.

Gothic Revival spread worldwide. Gothic elements were used in churches, universities, government buildings and even homes. When built in the 1840s, Trinity Church in New York and the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan—completed a century ago—lent the Gothic style to American architecture.

Neo-Gothic in the Modern World

Gothic influences continue today. Gothic features are to be found in some modern architects’ buildings. The Sagrada Família in Barcelona, designed by Antoni Gaudí and still being built nearly a century after his death, is a reimagining of Gothic ideas with modern materials and engineering.

Gothic Revival structures continued to be built for churches, universities, and institutional buildings. The style suggests tradition, immutability and spiritual or intellectual authority—assets a great many institutions want projected.

Gothic Architecture’s Lasting Impact

Engineering Innovations

Gothic builders were actually the first to invent such engineering practices that survive and continue to be used today. Their investigation of dynamic balance, structural support and material qualities paved the way for contemporary architecture. The concept of reinforcing external walls to compensate for the use of thinner walls and big windows would help shape ideas about skylines centuries later.

Artistic Legacy

Gothic art—sculpture, stained glass, the illuminated manuscript and metalwork—established some of the highest standards for beauty and craftsmanship. The idea that architecture, sculpture and art should collaborate in the creation of unified spaces was to determine later attitudes toward building design.

Cultural Significance

Gothic cathedrals still stand as potent symbols of what medieval Europe achieved. They epitomize what communities can achieve as well—working together, believing and dedicating. And these buildings endured conflicts, revolutions, fires and hundreds of years of use, further proof of human creativity and endurance.

Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame helped rediscover Gothic architecture’s importance. This rediscovery aided preservationists who succeeded in saving countless derelict medieval buildings from demolition. When Notre-Dame de Paris burned in 2019, people around the world grieved, reflecting just one part of these buildings’ enduring emotional and cultural relevance.

Preserving Gothic Heritage for Tomorrow

Restoring ancient Gothic buildings is a unique challenge. Stone erodes, stained glass softens and today’s pollution compounds the damage. Restoration involves a set of skills that are similarly specialized—from stonemasons to glaziers who know how work was done in the past.

Modern technology helps preservation efforts. Detailed digital records can be created with 3D scanning that aid restorers trying to understand the structure and devise a plan for repairs. When fire struck Notre-Dame, these digital records helped with planning the reconstruction.

Disputes emerge over how to repurpose Gothic buildings. Should restorers follow medieval techniques and use the same materials, or should they adopt modern methods that might be more effective? Should unsalvageable components be faithfully reproduced, or should modern insertions be easily identifiable? There aren’t easy answers to those questions.

Conclusion: A Time Transcendent Style

Gothic architecture developed from experimental work in 12th-century France, delivering some of the most current and stimulating new forms until it spread throughout every county where European civilization existed. It also advanced engineering that allowed taller, lighter and more lustrous buildings to be built. It also made spaces that were conducive to inducing awe and devotion. It united communities in collective creative pursuits.

The development of the Gothic style is an allegory to the stages of human development—innovation, simplification, regional variation, breakdown and revivescence. Every age has added fresh interpretation while adhering to the guiding premises that distinguished Gothic architecture and continue to make it distinctive: the balance between building and light, and the conjunction of artistry and technical skill.

And to this day, we still consider gothic cathedrals as some of humanity’s finest architectural creations. They serve as a reminder that with vision, skill and tenacity, people can produce things that will endure for centuries, prompting wonder in one generation after another. Even if you’re not religious, it’s hard not to feel something while standing inside a Gothic cathedral, connecting with centuries of human history, creativity and ambition—a lot to ask from buildings made of stone, glass and faith.

Frequently Asked Questions

What makes a building Gothic?

Gothic structures are characterized by their ribbed vaults, pointed arches, flying buttresses, and the extensive use of stained glass windows combined with a approximately 4:1 width to height ratio resulting in the characteristic high church aspect. These elements collaborate in tall structures with thin walls that have huge amounts of natural light within them.

How long did it take to construct Gothic cathedrals?

Construction for most Gothic cathedrals lasted 50 to 100 years, but in many cases it dragged on much longer. Cologne Cathedral spanned over 600 years from first stone to last rock, much of it in delay. These multi-generational enterprises took huge resources and commitment.

Why did Gothic structures have to use an abundance of stained glass?

Stained glass served multiple purposes. It did, however, let in natural light and a sense of the outside world while also generating a psychedelic rainbow effect. Those pictures in glass told religious stories to people who couldn’t read. Medieval Christians, during the time when polished glass was seen as protection and purifying (read: good) light, also considered light to be God’s divine presence—so stained glass was both a practicality and an extremely symbolic statement in stone.

What is the difference between Romanesque and Gothic architecture?

The Romanesque style of architecture that predates Gothic with its rounded arches, thick walls and small windows—its heavy building structures like fortresses. Gothic architecture brought with it the pointed arch, flying buttresses, and thinner walls with larger windows. Gothic structures are more airy, taller and open than the Romanesque ones.

Why is it called “Gothic”?

“Gothic” was an insult from the start. The term was employed by critics in the Renaissance to describe medieval architecture (it was associated with the Goths, Germanic tribes who sacked Rome). It was barbaric in style as opposed to classical Greek and Roman architecture, they thought. When the pejorative aspect of its description eventually waned, “Gothic” was left as the common label for this architectural mode.

Gothic cathedrals are built these days?

New Gothic cathedrals are few but not entirely unknown. In Barcelona, the Sagrada Família is still under construction, modelling itself on Gothic principles but employing modern means. Some churches constructed in recent decades are based on Gothic Revival or Neo-Gothic styles, combining the traditional Gothic appearance with a modern one. Nevertheless, classical Gothic design has continued to prompt modern varieties of religious construction in most cases.

What’s the tallest Gothic cathedral?

The title for the tallest Gothic church belongs to Cologne Cathedral in Germany with its 515 feet (157 meters) and twin spires. It was briefly the world’s tallest building when it was completed in 1880. Other towering Gothic buildings include Ulm Minster in Germany (530 feet, though it is not a cathedral proper), and Beauvais Cathedral in France, which reached for extreme height but partially collapsed.

How much was it to build a Gothic cathedral?

Exact costs are unknowable, but Gothic cathedrals were, in a word, hugely expensive—an amount commensurate with many millions or billions of dollars today. Towns had invested enormous wealth in these enterprises, often over generations. These prices consisted of material, labor, land price, tools/equipments and current repairing during construction period.